How to Navigate Power When Working to Create Change

In my third year of teaching, I came up with an idea I thought would solve one of the major problems facing the school.

In retrospect, it wasn’t that amazing and probably wouldn’t have worked – but I didn’t know that at the time!

I took the idea to my principal and was aghast when she said it wasn’t in the cards. Not only that, but it was clear she didn’t support it in any way, shape, or form. So I began lobbying: again and again I’d bring it up with her and share new reasons I thought it would work; I talked with colleagues and tried to get folks on board (with some success); I did more research and talked to principals of other schools who had found their own solutions.

In the end, I came across as annoying, probably defiant, and most certainly ineffective.

What I didn’t understand then – and what took me years to fully grasp – was that I was operating with a fundamentally flawed concept of how power actually works when it comes to creating the change we seek to make.

So let’s take a moment and go a bit deeper into how power moves.

Two Ways of Viewing Power to Create Change

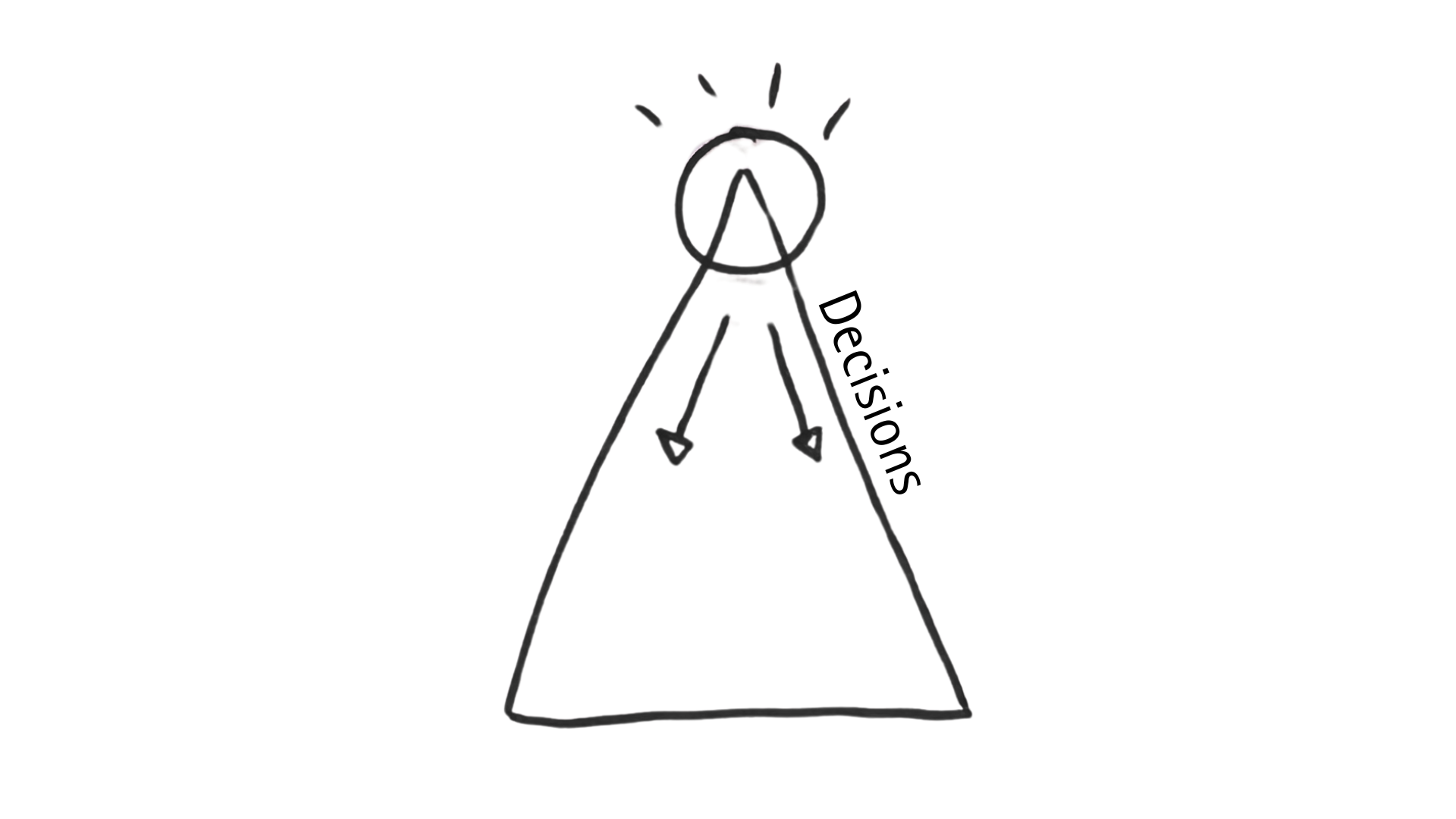

In the traditional view of power, which most of us were imbued with by textbooks, teachers, and our cultural myths and stories, power flows from top to bottom. “Those with power” sit at the top making decisions, while the rest of us find our home somewhere below in the hierarchy.

Work: The CEO at the top → Supervisors → everyone else

Politics: Big Money + Political Leaders → the rest of us

Schools: Principals → Teachers → Students

Families: Parents → Children

This view of power treats the person or people at the top as the main shapers and stakeholders of reality.

So if we want to make a change, what do we need to do? Change their minds (this is what I attempted to do with my principal) or replace them altogether (either through elections or overthrow.) This view of power leads us to focusing all our energy on the very top of the pyramid and trying to get a different result out of whoever sits there.

But while this view of power can seem true – this is not how power actually works.

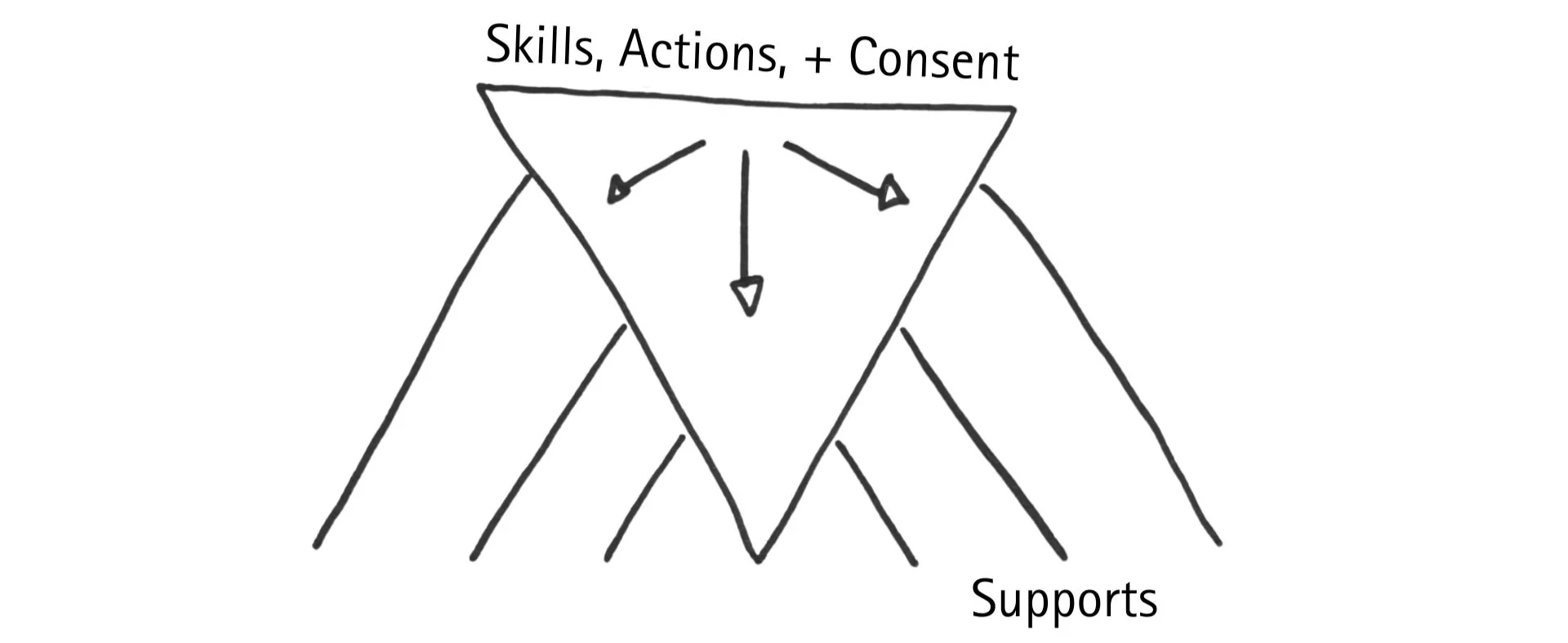

It is not nearly as set-in-stone or as stable as this model suggests. Instead, power looks a lot more like an upside-down triangle:

Power is inherently unstable and depends on the following to keep it upright and intact:

the skills, actions, and consent of those who are not "in power," and

various small-scale and large-scale supports and support systems.

When we think of Donald Trump, who and what allows him to have power? Republican leaders, business leaders, MAGA voters, people who stay silent, systems designed for the wealthy, and so on.

When we consider a Supervisor at work, where does her power come from? Other leaders, cultural norms around the title, workers afraid of being fired, workers who support her, etc.

It’s not their position at the top of the pyramid that gives him power – it’s that they are being supported by an ecosystem of people, businesses, and systems.

In other words: power does not flow from the top; it is created and maintained through the consent and participation of others.

Take a moment and think about something you want to change in your life, community, or broader society. Who or what has power in that context? What supports exist that maintain the current status quo?

So why is this important?

When we seek to create change, sometimes the best move isn't to use all our energy engaging with the "people in power." Instead, we might focus on challenging the supports that allow them to have power in the first place.

If we want to diminish existing power and the supports that uphold it, we can (among other things):

directly challenge support systems that maintain the status quo

identify and name examples of harm and their causes

question how + why decisions are made

provide alternative options and choices

leave harmful spaces, when possible

If we want to build power around a new idea or change, we can:

dream with others about alternatives and new ways of being and doing

organize and tell stories that bring connection and community

educate each other on what options + choices are available

develop alternatives and build consensus around them

participate in ongoing actions and conversations

The truth is, changework is often about doing both things at the same time. We diminish existing power structures by making it harder for its supports to continue. We build power by deepening our relationships and organizing new supports for new ways of doing things.

Mariama Kaba and Kelly Hayes write:

“By expanding our relationships and embracing interdependence, we can leverage power against the threats we face and extend care amidst crisis. We can courageously reach out and connect with other people, even if we feel like we don’t have much in common with them. When we experience a taste of collective power, our courage will grow, as we recognize that we are stronger together and that we are not alone.”

It’s easy to get overwhelmed if we think change only happens by changing the minds of those at the top – sometimes, that’s just impossible.

But when we lean into our communities, into building collective power, into developing the supports needed for change to take shape – that’s what can propel us and the change we seek to make forward.

This article is based on the excellent work of activist Daniel Hunter.